|

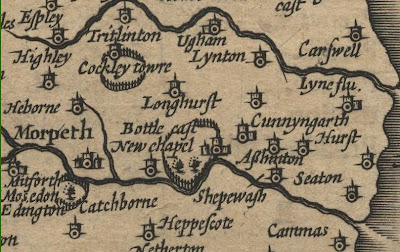

| Hartford House Location (click to enlarge) |

Enjoying a stroll through Plessey Woods Country Park, as many of us will have done, I found myself surrounded by vertical, towering rock as I meandered along the Pegwhistle Burn. Quite clearly this was a former quarry, but strange cuts in the rock, stretching the full height of the 40ft cliff, just below the Morpeth Road, caught my eye.

The 1st and 2nd editions of the Ordnance Survey mapping from the mid - late 19th century confirmed this to be the site of a quarry. The OS maps also clearly show a building to be in existence at the location of the unusual rock markings. Could this have been a building used for storage or even a dwelling that used the face of the quarry as one of its walls?

This newspaper article from 1859 is titled "The Smallest House in England":

What I have long known as "The Smallest House in England" is in Plessy Woods, the charming summer home of a Newcastle man of business. It has the charming woods all around it, and the "Well of St Keyne" at its door. As I have said it has the dimensions of a ship's cabin; and perforce of skilfull arrangement, the comforts of a mansion house.Janet Bleay in the booklet "Plessey: The Story of a Northumbrian Woodland" elaborates:

On the quarry wall you can see square holes at two levels which supported the floor and ceiling beams. This cottage was lived in until after WWII and the people kept a sweet shop which was entered from the side door off the Morpeth road. The coal shute is still there in the wall by the road. The cottage by the Pegwhistle Burn was small and it is just possible that this was the one described in the newspaper article.

|

| Ordnance Survey c1897 |

The 1841 census revealed Thomas Fryer (no relation) a quarryman and his family residing at Hartford Quarry House. William Watson, a cartman, and his family were also resident. There was, however more than one cottage in the vicinity of the quarry and this may have not been the "Smallest House in England" although it may not have started out as a three-storey building, that it clearly must have been at the time of it being a sweet shop. It may have had a vertical extension at some stage of its life. These 1899 auction notes describe it as:

Built on the edge of an old quarry and the top storey, which is accessible from the road, contains four rooms and pantry with out-offices; the lower offices which are alone accessible from the quarry, are at present used for dog kennels and store rooms.This was clearly an unusual and interesting building the use of which changed during its lifespan. The quality of Hartford stone from the quarry was highly valued. A newspaper article of 1859 mentions that the stone was used in the repairs to the Houses of Parliament and two London bridges.